Protecting and restoring Ann Arbor's natural areas and fostering an environmental ethic among its citizens.

Park Focus: Traver Creek Watershed

Scott Spooner, Golf Course Superintendent

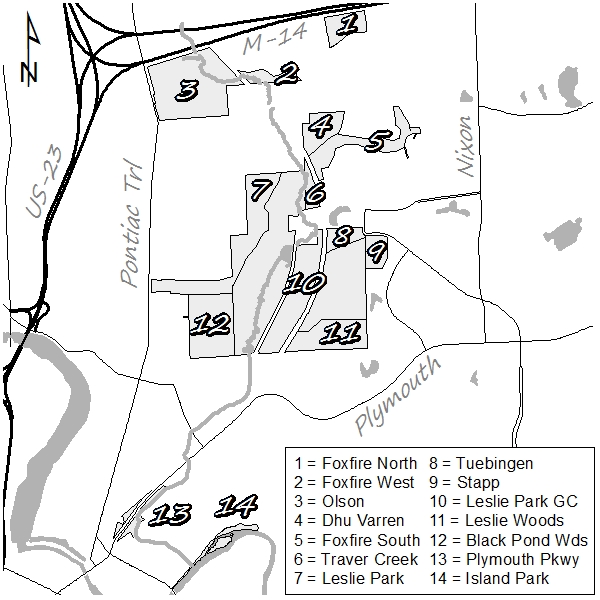

Traver Creek is a tributary of the Huron River whose watershed extends from north of the M14/US23 interchange to where the creek enters the river, just upstream of Island Park. This area includes these parks and natural areas: Foxfire North, Foxfire West, Foxfire South, Olson, Leslie, Tuebingen, Plymouth Parkway, Traver Creek, Dhu Varren, Stapp, Leslie Woods, and Black Pond Woods, as well as Leslie Park Golf Course. The seven square miles that drain into Traver Creek range from agricultural lands in the north to more urban and residential areas as the creek nears the Huron River. In the last 15 years, residential growth in the watershed has accelerated and with it, an increase in the amount of

hard, impervious surfaces which channel precipitation directly into the creek. This causes the creek to have very high flows immediately after rains and much less water during dry periods.

Photo: Scott Spooner

As superintendent at Leslie Park Golf Course, I am intimately familiar with Traver Creek, as it winds through the golf course between holes 10 and 13.There are also two ponds fed by the creek, on holes 12 and 17. In 2013, the city partnered with the Washtenaw County Water Resources Commissioner to regrade and stabilize the creek. The two ponds were deepened to allow for increased storage during high rainfalls. The water will now slow down in these ponds, allowing any sediment the runoff has picked up to fall out. Along with decreasing the amount of soil that is lost, it also spreads out the amount of water that heads downstream over a longer period of time, decreasing the potential for flooding.

This project also created 6.5 acres of wetlands on the golf course with a total of 10.2 acres of the disturbed area replanted with native vegetation, which will be maintained through controlled burns. The area 10 to 50 feet from creek banks is not mowed like the rest of the golf course but kept as a buffer strip of native plants. This strip of vegetation traps sediment and enhances filtration of nutrients and pesticides by slowing down runoff that could enter Traver Creek. The root systems of the native plants stabilize the banks and provide protection against erosion.

An additional benefit of the project was that a tributary originating in Black Pond Woods, designated the Arrowood Branch after the nearby subdivision, was brought above ground after being buried in an underground drainage pipe for 40 years. The project hopes to prevent 687 tons of sediment from being deposited in the Huron River. This $1.7 million undertaking was funded by the city and county stormwater funds, with the State of Michigan Department of Environmental Quality offering up to 50 percent loan forgiveness due to environmental benefits of the project.

If you take Leslie Park Golf Course and the eight parks and nature areas that surround it as one unit, it is the single largest greenspace within the city of Ann Arbor. At nearly 375 acres, it can support a wide range of wildlife with the golf course serving as a vital habitat corridor connecting the various nature areas with each other.

Coordinator's Corner: Future Forests

David Borneman, Deputy Manager for Volunteerism and NAP

For the past 18 years, I've tried to be a good father. Myself the youngest child, I never had any younger siblings to care for; never even babysat. Still, I surprised myself by recognizing that I did have some innate sense of how to care for my children. So I set out trying to steer my kids down the path that I thought they should follow. That worked fine for awhile, as long as the path I selected happened to coincide with their own path. But eventually I realized – as all parents do – that my path was not their path, and that my real role as a parent was simply to allow them to choose their own way through life, and to encourage and support them on that journey.

I reflect on this as my daughter graduates from high school and embarks, a bit more independently now, on her own journey through life. Of course I will still be there for her; my role as parent will never end. But my specific responsibilities have changed. I'm no longer driving; I'm offering navigational suggestions. And I'm watching out for unanticipated impacts that could knock her off course. There is still some value to the experience that comes with my longer life.

Twenty-one years ago, I began another sort of "parenting" role. With the help of many eager volunteer botanists, we began inventorying our park natural areas, and developing stewardship plans to guide our care of them. I suppose I viewed some of those parks as my "children" and felt responsible for guiding their succession. But now, 20 years later, I am reconsidering some of those plans and whether we have too strongly tried to impose our will on them, pushing them down a predetermined course that may not make sense in the long-term. I'm thinking specifically of some old field areas that were once farmland and had, by the early 1990s, begun filling in with shrubs. Because most of those shrubs were invasives like buckthorn and honeysuckle, it made sense to remove them to maintain the open field habitat that park users and grassland birds enjoyed. Thus began two decades of burning and cutting to keep the shrubs at bay and maintain those old field areas.

The problem is, we're losing that battle. I hadn't fully realized that until recent walks with new staff to clarify management goals for these sites. But taking a fresh look at the situation, I had to ask myself whether that original goal still makes sense. Ecosystems don't "choose" their path through life the way my human children do. But there certainly are ecological processes in place that drive them toward a more wooded condition than existed 21 years ago. Perhaps it is time to accept that nature has a different "plan" for those areas than I originally envisioned. We still need stewardship there. Invasives and fire suppression still threaten to derail natural ecological succession. But we may need to accept that yesterday's old fields will be tomorrow's forests. We may need to change our role as Stewards of these areas.

Ospreys on the Huron River

Dea Armstrong, Ornithologist

Ospreys are the best fishermen in the world. These fish-eaters hover over their potential prey and then plunge feet-first, head-second (yes, it is possible!) into the water. That they can lift their prey out of the water (it can weigh as much as 30 percent of the bird) and then turn the fish into an aerodynamically efficient position as it flies back to a perch is remarkable. It is no small wonder then that a program to help Osprey numbers increase in Michigan has been closely followed by more than just birdwatchers. As part of our mission to protect and restore Ann Arbor's natural areas, NAP along with help from the Huron River Watershed Council, ITC (a corporate community partner) and Washtenaw Audubon Society, is planning to put up several Osprey nesting platforms along the Huron River to continue what the folks of Michigan Osprey (formally Osprey Watch of Southeast Michigan) have started.

Photo: Mark Medcalf/Shutterstock

Ospreys were once hunted in Michigan. Then, in the mid-20th century, the pesticide DDT began to have a tremendous impact on the nesting success of Ospreys along with all other raptors (meat-eating birds) that are high on the food chain. Hunting of Ospreys and DDT use are illegal these days and all raptors are doing better. In fact, Kensington Metro Park has exceeded their goal of introducing 30 new pairs of Osprey in Southeast Michigan. Unfortunately,

Ospreys have also taken to nesting atop cell towers, building nests that can interfere with communication equipment. Nesting platforms in appropriate habitats would definitely be a better idea than nests on top of a mass of wires and electrical equipment.

We wondered if we could do for Ospreys what we did for Eastern Bluebirds, namely, create nesting spaces for them. All across the United States, Peregrine Falcons, Eastern Bluebirds and Chimney Swifts have been quite successful nesting in man-made structures or nest boxes. NAP has had great success with its Bluebird houses. Bluebird populations have grown so much that Bluebirds are now also nesting in natural cavities at parks where the birds did not occur until we put up nest boxes. Similarly, Ospreys have taken to nesting platforms at Kensington Metro Park and in multiple sites all over the country. If we were to provide a nesting platform in a safe area along the Huron River, perhaps an Osprey would come to nest along the Huron River in some of our parks.

With advice from Barb Jensen of Michigan Osprey, multiple sites along the Huron River in Ann Arbor parks were proposed as locations where nesting platforms could be installed. The sites that were eventually selected (Furstenberg and South Pond) will provide easy access for viewing the nests as well as some "privacy" for the Ospreys from active river users during the critical times of nest building and incubation.

There will be plenty of time for viewing the nesting birds as the pair takes turns sitting on the eggs (2 to 4 of them) for 30 to 40 days. Once the eggs hatch, both parents will feed the birds for almost 2 months, giving photographers many opportunities for action shots!

As I write this article in April, Osprey are returning to Michigan and looking for nest sites. Hopefully, some 2 year old Osprey will investigate our platforms and find them tempting for next year (Ospreys don't nest until they are 3 years old or older). We hope to soon have Ospreys nesting in our parks and promise to keep you posted!

For more information about Ospreys in Michigan, visit Michigan Osprey's website at

http://michiganosprey.org/.

NAPpenings

Welcome, new Park Stewards!

Kristen Schotts - Huron Parkway

Thank you!

Many thanks to the groups who volunteered with NAP recently. We could not make such a difference without you!

Ann Arbor Pack 5 Cub Scouts

Ann Arbor Spartans

Comcast

Community High School

EMU Vision

MCA Girls Youth Group

Middle College National Student Leadership Conference

Pioneer High School

Interact Club

Temple Beth Emeth

University of Michigan:

Alpha Phi Omega

Econ 108

Epsilon Delta

School of Information

United Way

YMCA Youth Volunteer Corps

Deer Management

NAP staff had a new experience this past winter: counting deer from a helicopter! In the spring of 2014, City Council directed city staff to develop a deer management plan. To obtain population estimates, three NAP staff squeezed into a tiny helicopter twice early in the year and visually counted deer from above. We found that the majority of the deer in Ann Arbor are in Wards 1 and 2. For more information about the deer management plan and our aerial surveys, visit:

www.a2gov.org/deermanagementproject.

Staff Updates

Welcome…

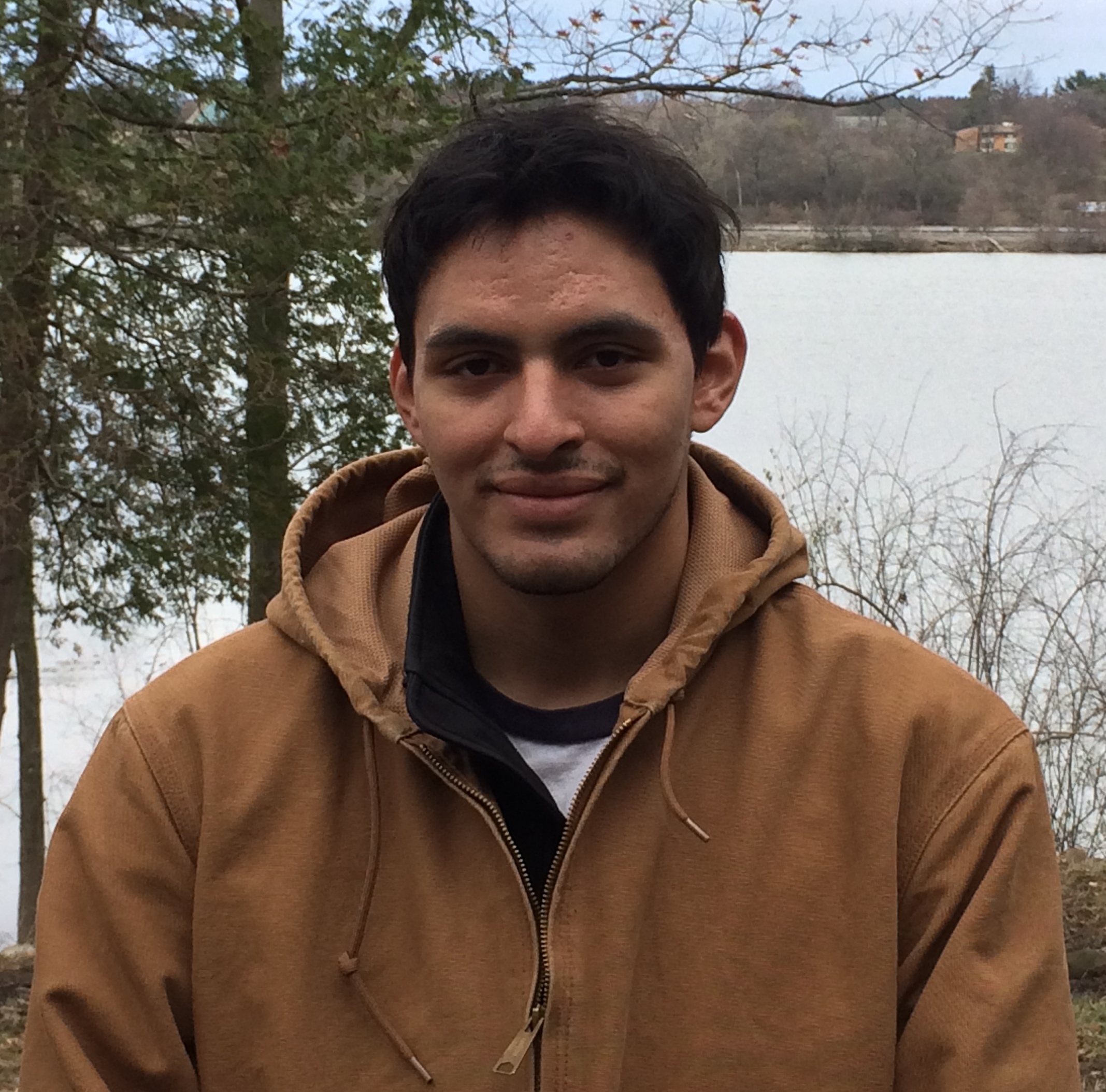

Rafael Contreras-Rangel, Field Crew

Rafael Contreras-Rangel, Field Crew

I have recently graduated from Kenyon College after studying biology and environmental studies. All of my time at college I've been preparing to do conservation work, and I am excited to finally be able to do that with NAP. Before joining the field crew I used to work as a volunteer, so I am also excited to lead some work days and get to know more like-minded people!

Liz Banda, Field Crew

Liz Banda, Field Crew

I graduated from Michigan Technological University, with a degree in Wildlife Ecology and Management. For the past 5 years, I have been working in Ann Arbor at an environmental research institute applying GIS and remote sensing techniques to assess wetland ecosystems. I am very excited to be working for NAP as part of the field crew and can't wait to meet the many enthusiastic volunteers in the community along the way!

Farewell…

Drew Zawacki, Field Crew

Drew Zawacki, Field Crew

Over the past year, I have enjoyed working to help restore Ann Arbor's natural areas and getting to know some awesome people. I'm sad to go, but look forward to using the knowledge I've gained when I move to Wisconsin to begin a job with the National Parks Service. I will miss the crew and working with NAP's amazing volunteers.

Rachel Nagel, Field Crew

Rachel Nagel, Field Crew

I thoroughly enjoyed my time on the field crew and I will miss working with NAP staff and volunteers. Sadly, I am moving on and starting a new job with an environmental consulting company in Detroit. I am grateful for all that I have learned and for the opportunity to educate others about nature and conservation in Ann Arbor. A big thank you to everyone I've met along the way!

Invasive Alert: Japanese Hedge Parsley

Tina Stephens, Volunteer Outreach Coordinator

There's a new invader on the loose! Japanese hedge parsley (Torilis japonica) has been spotted in pockets in Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin and has even been found in a couple of our beloved Ann Arbor Parks. Some folks, like the Invasive Plants Association of Wisconsin, are predicting that it has the potential to be even worse than our much-hated garlic mustard. One of the features making it such a potentially prolific invader is its "Velcro-like" seeds (see inset photo) that can easily stick to clothing and fur and travel great distances. If we have any hope of keeping it under control or eradicating it, now is the time to learn to identify it, report it, and pull it.

Much like garlic mustard, Japanese hedge parsley has a two-year life cycle. To identify Japanese hedge parsley, look in disturbed areas for first-year rosettes that are low, alternate, fern-like, 2-5 inches long, and slightly hairy (see photo to the right). In their second year, it can be identified by 2-4 foot tall wispy, white, Queen Anne's lace-like florets blooming in July and August (see bottom left photo). After flowering, the fruit ripens quickly into seeds that are covered in hooked hairs (see bottom right photo).

The most effective method for treating Japanese hedge parsley is to pull it, bag it, and put in the trash or send it to the municipal compost facility. Mowing prior to flowering may also be effective. If you find it in a City of Ann Arbor natural area, please let us know. If you find it elsewhere, you can report it to the Great Lakes Early Detection Network at

www.gledn.org or Midwest Invasive Sepcies Information Network at www.misin.mus.edu.

Photos: Kristian Peters / Fabelfroh 07:58, 07:59, 08:00 / 14 September 2007 / Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons