Natural Area Preservation News

Protecting and restoring Ann Arbor's natural areas and fostering an environmental ethic among its citizens.

Volume 22, Number 2

Summer 2017

Park Focus: Fuller Park

Becky Gajewski,

Stewardship Specialist

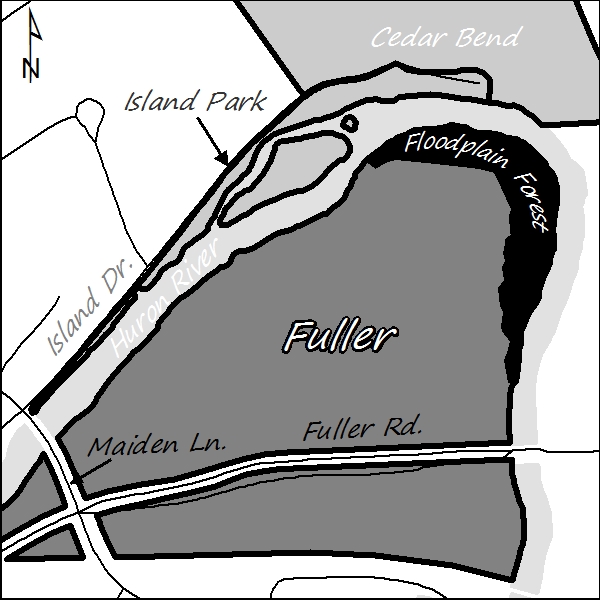

When you think of Fuller Park, you may think of cooling off in the pool, zipping down the water slide, or playing a game of soccer. But did you know that Fuller Park also has its own natural area? North and east of the soccer fields, a floodplain forest curves around with the bend in the Huron River, and extends all the way down to Fuller Road. A small foot path begins at the bridge that leads to Island Park and runs along the edge of the river, all the way through the forest.

The path begins up on a bank above the river, but very shortly, it drops down and enters the river floodplain. A floodplain is a flat area next to a river that floods when the river is high. This flooding usually happens following big rain storms or when the snow melts in the spring. The floodplain forest at Fuller is full of interesting features you can only find along a river, and they tell a story about the natural processes that happen here.

The path begins up on a bank above the river, but very shortly, it drops down and enters the river floodplain. A floodplain is a flat area next to a river that floods when the river is high. This flooding usually happens following big rain storms or when the snow melts in the spring. The floodplain forest at Fuller is full of interesting features you can only find along a river, and they tell a story about the natural processes that happen here.

One thing you might notice while walking down the trail is that the trees here are different than in most of Ann Arbor's other natural areas. A stately patch of sycamores, a characteristic tree of the floodplain, sits right at the beginning of the trail. One of the easiest trees to identify, the bark at the base of the tree has a tan alligator skin-like appearance, which changes as you look up the trunk. This bark transitions into a patchwork of gray, blue, white, and yellow patches, which eventually get smaller and change into smooth, flat, bright white bark, almost making the top of the tree look dead when its leaves are gone. Other floodplain trees you can find here are cottonwood, elm, bur oak, and willow. These trees don't mind "getting their feet wet" along the river.

The trees in the floodplain have evolved a safety mechanism that helps keep them from being washed away during heavy flooding. While you're out on the trail, take a look at the bases of the trees. You will notice that many of them widen, or flare out, at the bottom. Flared roots help keep the tree stable, which is especially important when floodwaters are rushing past. While you're examining the bottoms of the trees, check out the ones closest to the river. You may be able to see a layer of dried mud on the bottom portion of the trees and on the vegetation around them. That mud was deposited during a flood. You can get an idea of how deep the floodwaters were by looking at how far up the trunk the mud reaches.

The trees in the floodplain have evolved a safety mechanism that helps keep them from being washed away during heavy flooding. While you're out on the trail, take a look at the bases of the trees. You will notice that many of them widen, or flare out, at the bottom. Flared roots help keep the tree stable, which is especially important when floodwaters are rushing past. While you're examining the bottoms of the trees, check out the ones closest to the river. You may be able to see a layer of dried mud on the bottom portion of the trees and on the vegetation around them. That mud was deposited during a flood. You can get an idea of how deep the floodwaters were by looking at how far up the trunk the mud reaches.

As you continue down the trail, you will eventually start to see low ridges paralleling the river. These formations are created during a flood when the rushing water of the river rises above its banks. As the water spreads out over the floodplain, it slows down, allowing any sediment it's carrying to drop out. Over time, that sediment builds up to form ridges and mounds. If it has rained recently, you may also see elongated low spots filled with water along the trail. These are called meander scars, and they mark a place where the river channel used to be. Rivers are continuously bending, curving, and changing their paths due to erosion and deposition of sediments from place to place.

Although the floodplain forest can be a chaotic and changeable place, many critters are quite happy to call it home. Wood ducks occasionally nest in the forest, as do woodpeckers and other birds that make their homes in tree cavities. Gray squirrels, chipmunks, and groundhogs forage for food under the leaf litter. Frogs sing on warm, damp evenings, and deer pass through on their daily routes through town. In the springtime, carpets of trout lilies and patches of violets and bloodroot bloom among the previous year's fallen leaves. Next time you find yourself at Fuller Park for a dip in the pool or a baseball game, take a wander out through the natural area and explore the floodplain forest. There is much beauty to be found in the changes that happen here throughout the year.

Coordinator's Corner: Details, Details, Details...

Dave Borneman, Natural Area Preservation Manager

I'm getting married in June, perhaps at about the time you're reading this article. June's a popular time for a wedding, given the beautiful weather, blooming flowers, and the start of summer vacation. I knew that. What I didn't know was just how much preparation and work is required to pull off a wedding! So many details to work through: venues, caterers, flowers, dresses, music, vows, etc… etc… etc… It's been a very busy few months for those working so hard to pull this together, mainly my fiancée!

Now, a wedding is certainly a big deal, a once-in-a-lifetime sort of thing. So of course it requires a lot of work and a huge amount of planning. But perhaps you've never really stopped to think just how much planning and preparation goes into pulling off the many dozens of workdays, prescribed burns, and other volunteer events that NAP hosts every year. Consider, for example, our prescribed burn program. You may get a text at 9:00 a.m. inviting you to participate in a burn with NAP that afternoon. But long before that text was sent, and long before you show up with your leather boots to work on the day's burn crew, the staff, park stewards, and other dedicated volunteers have been putting together the plans and working out the details to make that burn possible.

It's an on-going process, but let's just jump in and start in the middle of the field season, when staff and Park Stewards are out in their parks. We're taking note of how areas are looking, where there are infestations of invasives that need attention, and where controlled fire might be an appropriate restoration tool to deploy. Later that winter, those field observations come into consideration when we develop lists of potential prescribed burn sites. Then there's a long list of controlled burn plans, burn permits, neighbor notification letters, park signs, and burn crew training that needs to be accomplished before burn season actually starts. And then it's a matter of monitoring the weather, checking field conditions (often early in the morning at first light!), getting equipment ready, prepping individual sites, notifying volunteers and others, etc… that all must happen before the first volunteer ever shows up for the burn.

It's a different but similarly rigorous process that goes into every one of our workdays, some of which are quite large, involving hundreds of students from local schools. If we're doing our job well, the burn or the workday goes off without a hitch, and everyone comes and goes safely and efficiently after the 3-hour event. But know that, for every hour of field time spent by a volunteer at a NAP event, there are many, many other hours of behind-the-scenes work that went into making that event happen. Most of those logistical hours are put in by hard-working NAP staff, but not all of them. We benefit greatly from volunteers who help lead other volunteers, who organize and run workdays, who lead nature walks, and who work in the office doing administrative tasks. All of these efforts contribute to the success of NAP's big events.

So the next time you're participating in a burn, or a big workday, or another big NAP event, please take a moment and thank those who helped make it all happen. And if you're one of those gifted individuals who likes to help make things happen, we hope you'll consider becoming an official workday leader with NAP.

European Water Clover: Unlucky Four-Leaf Clovers

Mike Hahn, Stewardship Specialist

Have you ever found a four-leaf clover? I have never been so lucky, but it's not always cause for celebration if you do. Last summer, the Michigan Department of Natural Resources identified two populations of European water-clover (Marsilea quadrifolia) where some of our parks meet the Huron river. There is currently one in Barton Pond, along Barton Nature Area, and another in Argo Pond, adjacent to Argo Nature Area. This clover may have four leaves, but it is a decidedly unlucky find. It is an invasive species that degrades native aquatic habitat and vegetation.

European water-clover is European in origin, as the name implies, but it can also be found in Asia. Its leaflets resemble those of a four-leaf clover (despite belonging to the fern family) and usually float near the water's surface. It can also be found standing tall as an emergent plant. The leaves are smooth and can adjust their angle towards the sun. Rhizomatous roots help it form dense mats in shallow, slow-moving rivers and ponds, and any root that breaks off will easily establish new populations. All of these attributes combined make it a plant that easily outcompetes native aquatic vegetation.

European water-clover is currently a "watch list" species, which means it is still allowed to be sold commercially. Despite its wide availability, it is only present in three other Michigan counties besides Washtenaw, according to the U of M Herbarium. This is why it is so important to address the populations in our parks before they spread farther through the Huron River watershed.

We have been coordinating with the Michigan DNR for the past year to come up with solutions to the problem. The DNR's plan of action includes the installation of benthic mats over both populations of European water-clover. This is a mechanical control method that smothers the plants, much like using a tarp or cardboard to suppress weeds in a garden bed. Benthic mats are made out of biodegradable jute fiber, which reduces negative impacts on the environment compared to other control methods. The largest mat will cover an area of about 1000 square feet in Argo Pond, and a smaller mat covering about 350 square feet will be installed in Barton Pond. Both will be anchored to the lake bed with sand bags. The mats will be submerged, but there may be some visible sections along the shoreline, covering exposed mud.

If you would like to learn more about aquatic invasive plants or invasive species in general, Michigan's invasive species program is a helpful resource. This cooperative program is managed by several different state departments, and offers information about common weed species like phragmities as well as newer invaders like European water-clover. You can check it out at

michigan.gov/invasives.

Garlic Mustard Pesto Recipe

Madison Roze , Outreach Assistant

You may know invasive species are bad for native ecosystems, but did you know that some of them can be incorporated into your diet for a healthy, flavorful shot of vitamins and minerals? Wild plants often have higher levels of nutrients than their cultivated counterparts. Garlic mustard for instance, infamous for its aggressive growth patterns, is high in essential minerals, proteins, and vitamins A and C. So next time you pull it, don't toss it in the trash just yet! Bust out the food processor and make some pesto instead.

INGREDIENTS:

INGREDIENTS:

· 11 cups packed garlic mustard leaves, coarsely chopped.

· 1/4 cup pine nuts

· 2 garlic cloves

· 1/3 cup grated parmesan cheese

· 1 cup extra virgin olive oil

· 1/2 teaspoon sugar

· coarse ground black pepper, salt, and lemon juice to taste

INSTRUCTIONS:

1. In a blender or food processor, pulse together the pine nuts, garlic and cheese.

2. Slowly add the garlic mustard leaves, a little at a time.

3. While the blender/food processor is on, add the olive oil in a steady pour over the course of one minute or until the consistency is to your liking.

4. Add lemon juice, sugar, pepper and salt to taste. Blend until mixed.

You can add this to pasta, have it on toast, with a meat dish, or anywhere you would normally use pesto. Happy foraging!

NAPpenings

GARLIC MUSTARD MUNCHERS

Have you noticed a bunch of small holes in garlic mustard leaves this year? Argo Park Steward Rob Davenport first brought this to our attention in mid-April and then we started seeing them in a several of our other parks! Rob was able to catch an insect in the act of the

Have you noticed a bunch of small holes in garlic mustard leaves this year? Argo Park Steward Rob Davenport first brought this to our attention in mid-April and then we started seeing them in a several of our other parks! Rob was able to catch an insect in the act of the

munching one of these holes and sent the offender off to the USDA for identification. They confirmed that he had captured a flea beetle,

Phyllotreta ochripes, and that this was the first time it has been officially confirmed in the U.S.! Researchers in Switzerland considered this beetle as a candidate for a garlic mustard biocontrol, but their diet isn't specific enough to garlic mustard, and it was feared they may also damage commercial legumes. Because this is all very new, there is some natural skepticism as to if this really is

Phyllotreta ochripes so the next step is to collect some samples of the insects and send them off to Italy for confirmation. If you notice small holes like those pictured in your garlic mustard leaves, look for this beetle and let us know if you see them. You can email us at [email protected] or call 734.794.6627.

munching one of these holes and sent the offender off to the USDA for identification. They confirmed that he had captured a flea beetle,

Phyllotreta ochripes, and that this was the first time it has been officially confirmed in the U.S.! Researchers in Switzerland considered this beetle as a candidate for a garlic mustard biocontrol, but their diet isn't specific enough to garlic mustard, and it was feared they may also damage commercial legumes. Because this is all very new, there is some natural skepticism as to if this really is

Phyllotreta ochripes so the next step is to collect some samples of the insects and send them off to Italy for confirmation. If you notice small holes like those pictured in your garlic mustard leaves, look for this beetle and let us know if you see them. You can email us at [email protected] or call 734.794.6627.

CITIZEN BAT MONITORS NEEDED!

NAP has been accepted as a partner organization with the Organization for Bat Conservation's Citizen Bat League! As part of their volunteer Bat Monitoring Program, NAP will train volunteers to record bat calls while driving along preset routes in and around the city.

All monitoring equipment will be provided, and the surveys will take place on one night in June and one night in July. Would you like to be involved? Let us know at [email protected]!