Prothonotary Warblers at the nest cavity in Gallup Photo by Keith Dickey

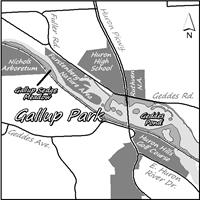

When Ann Arborites think of our park system, the first place that comes to mind might be Gallup Park. A popular spot for nature lovers, picnickers, runners, walkers, playground users and boaters, Gallup hosts one of the City's two canoe liveries, two great playgrounds, miles of paved trails, picnic shelters and a turtle-nesting mound. This park was named for Eli Gallup, who was the Ann Arbor Parks Superintendent in the early 20th Century. It was under his watch that many of the dams and adjacent land along the Huron River were acquired and developed as parks. However, outdoor enthusiasts don't always know about Gallup Park's other treasures—including the sedge meadow and Geddes Pond, where native plants, birds and other animals thrive.

Many uncommon species of nesting birds call Gallup Park home, particularly in the sedge meadow, a unique treasure in the Ann Arbor park system. Find the wet meadow by walking west on the Gallup pathway from the wooden car bridge for about 10 minutes. Native plants, such as tussock sedge, mountain mint and Culver's root are adapted to this habitat and support many insects, which feed birds galore.

For several years, Willow Flycatchers have made their home in the sedge meadow. These small greenish birds sally forth from a branch, over the grasses and sedges, catch an insect, and bring it back to the same branch to consume it. They build their small, cup-shaped nests low in willows and other shrubs, and can be seen from late May through July, often calling fitz-bew, their distinctive song. They are uncommon in our parks, only generally found nesting here, Olson Park and Furstenberg Nature Area. NAP's work preserving and restoring this natural area helps this scarce bird species to thrive.

Standing dead trees along the water's edge in the sedge meadow provide the perfect habitat for Downy Woodpeckers. This year, a pair of Prothonotary Warblers chose an old Downy Woodpecker hole for their nest. The Prothonotary Warbler is the only cavity-nesting warbler species in the Eastern U.S., a bright golden insect-eater with gray wings, whose preferred breeding habitat is a hole in a tree hanging over the water. Prothonotary Warblers are listed in Michigan as a species of special concern, so providing the right conditions for them to nest in our parks was a huge win! Since Michigan lies at the northern edge of their customary breeding range, the birds are naturally scarce. But, a small population established itself several years ago on the Huron River at Hudson Mills Metropark just west of Ann Arbor, and the population continues to spread downstream. Last year they nested in an Ann Arbor park for the first time, in Forest Nature Area. This year they returned to Forest and also moved into the Gallup sedge meadow, where they delighted many bird lovers. The best way to see Prothonotary Warblers is by boat. Luckily, you can rent a canoe, kayak or paddleboat right at Gallup Park Canoe Livery. The male warbler's loud sweet-sweet-sweet-sweet song alerts us to the birds' location and helps us to see this tiny songster (photo on page 1).

In winter, Gallup Park really shines. The open water at Geddes Pond can be an ideal place to view wintering ducks and other waterfowl. Rafts of Common Mergansers, with their green or rusty red head-feathers, make Geddes Pond their temporary home. Other diving ducks, such as Canvasback, Redhead, Scaup and Bufflehead, can be seen searching the waters for fish and invertebrates. Often a raptor, such as a Merlin or Cooper's Hawk, will make its winter home here too, feeding on the bounty of small songbirds that shelter in the berry bushes at Gallup. In recent years, a Northern Mockingbird has overwintered at Gallup, feasting on berries and delighting passing walkers. Maybe we will see her again this winter in Gallup Park, Ann Arbor's most renowned park.

To help protect the Gallup sedge meadow from invading shrubs, join our workday on Monday, February 17th from 1 to 3 p.m. See page 4 for details.

Coordinator's Corner: Keep Up the Good Work!

Dave Borneman, Natural Area Preservation Manager

Climate change has finally become mainstream. Everybody is talking about it, and for good reason, as it threatens drastic changes to our planet. It's been the subject of numerous presentations at recent ecological conferences. But as the discussion spills over from the scientific community to the general public, there's a risk of it being misrepresented, or at least oversimplified. So I thought I'd weigh in here with my own thoughts about what climate change will do to the restoration work we undertake here in our little corner of the planet. This sort of crystal ball-gazing is always dangerous, as I risk having my current predictions read with horror by future generations. But here goes…

Climate change will undoubtedly bring profound changes to many parts of the planet, in ways far too numerous and complex to expound on here. In Michigan, the changes seen during our lifetimes may well be far less than in many other locations. I do expect that things will be warmer overall, and weather events will be more extreme. So, how are we as ecological restorationists preparing for these changes? Are we planting our parks with seeds native to Tennessee? Or converting our oak-hickory forests to longleaf pine ecosystems? Nope. None of us alive today will see range shifts that extreme. In recent decades, plant and animal ranges have shifted north about one mile per year, on average. It's 45 miles south to Toledo, and about 90 miles to Findley, Ohio. So if Appalachian ecosystems are ever going to shift north as far as Ann Arbor, it's not going to happen in the near future.

No, let's not give up quite yet on our own resilient native southeastern Michigan ecosystems. Now is not the time to abandon them; now is the time to strengthen them! We've already been invaded by Japanese Stiltgrass, a weed formerly found mostly in the southeastern U.S. We can expect that others will follow, some spurred on by climate change. The more we do to keep our native forests, savannas, prairies, and wetlands healthy now, the more resistant they will be to invasives in the future.

In Michigan, we may very well need to welcome some plant and animal species whose previous range didn't quite extend this far north. And we may be unable to hold on to other species who can no longer survive this far south. But we don't yet need to say goodbye to our oak-hickory woodlands, or our other native ecosystems. They will be with us through our lifetimes, barring some other unforeseen ecological disaster. And the restoration work we collectively do today will continue to pay big dividends tomorrow, and for years to come. The pollinator gardens we tend today will continue to nurture our native pollinators. And the tiny acorns we plant today will grow into grand old oaks that will still find the climate of Ann Arbor acceptable far into the future. The threat of climate change to our planet is real; but don't let that distract you from the good work we're all doing here today.

Winter Tree Identification

Becky Gajewski, Stewardship Specialist

Folks don't normally think of winter as a great time to practice plant identification. After all, the flowers and grasses are dormant or covered with snow and the trees have lost their distinguishing leafy features. But winter can actually be one of the best times to learn to identify trees because you can do so based on their bark and buds, which they keep all year round. Read on to see how you can identify common groups of trees by their bark and buds after the leaves have fallen.

Oaks:

The most common oaks in our woodlands are red, black, and white oak. If you can get a look at the buds, they usually appear in clusters on the ends of the twigs. White oak buds are rounded at the tips, like a little clump of bird eggs, while black and red oak buds are pointed. On mature trees, white and black oak bark has a distinctly blocky pattern. Black oak's bark is dark gray (“black"), while white oak's bark is light gray (“white"). Red oak's bark isn't blocky, rather, it has long, vertical ridges of light gray with dark gray in between. It looks as though someone took an iron and flattened out the ridges.

|

|

|

|

White oak and red oak buds

| White oak bark

| Black oak bark

| Red oak bark

|

Hickories:

As with the oaks, we have three common species of hickory in our area: bitternut, pignut, and shagbark hickory. Bitternut hickory is most easily identified by its buds, which are long, pointed, and bright sulfur yellow in color. The bark of this tree is a little trickier to distinguish, but it is gray and separates into shallow cracks and narrow, crisscrossing ridges. When I was learning to identify this tree, we called the shapes in the bark “crystal latticework." Shagbark hickory is very easy to identify. As its name implies, its bark has a very shaggy appearance, separating into long, rough plates that curve away from the trunk on one or both ends. Pignut hickory can look similar to bitternut or like a mix between bitternut and shagbark, but it does not have the sulfur yellow buds, and its bark may occasionally separate into small loose strips.

|

|

|

|

Bitternut hickory bud

| Bitternut hickory bark

| Shagbark hickory bark

| Pignut hickory bark

|

Cherries:

There two species of cherry that commonly grow to full-sized trees size in our area. They are black cherry and sweet cherry. Black cherry is a native tree whose bark is dark gray, almost black, and broken into thick irregular plates that curl up on the edges, resembling burnt potato chips. Sweet cherry is not native, and it has dark gray bark that sticks tight to the tree and is covered with conspicuous horizontal lines, called lenticels, which help the tree with gas exchange.

|

|

Black cherry bark

| Sweet cherry bark

|

Others:

Two more trees with conspicuous bark are ironwood and musclewood. Ironwood is a small- to medium-sized tree with soft, thin, grayish-brown bark that peels into loose strips, giving it a shredded appearance. Some call this “cat-scratch bark." Musclewood is a small tree or large shrub with thin, smooth, dark bluish-gray bark that can be spotted with lighter or darker patches. It gets its name from the distinctive muscle-like ridges running down its trunk.

|

|

Ironwood bark

| Musclewood bark

|

For more information about identifying these trees (and many more) check out the book Michigan Trees by Burton V. Barnes and Warren H. Wagner, Jr.

NAPpenings

Welcome, new Park Steward!

Gabbie Buendia, Cedar Bend Nature Area

Thank You!

Thank you to the local organizations that donated prizes for our Volunteer Appreciation Potluck!

Bløm Meadworks

City of Ann Arbor Canoe Liveries

City of Ann Arbor Golf Courses

The Creature Conservancy

Downtown Home and Garden

Michigan Wildflower Farm

Motawi Tileworks

Real Seafood Company

Many thanks to the gropus who volutneered with NAP recently. We could not make such a difference without you!Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

Concordia University

Deloitte Consulting

Eldor Automotive Powertrain

EMU Catholics on Campus

EMU Conservation Biology Class

EMU Early College Alliance

Geocaching CITO

Greenhills School

Mathematical Reviews

Michigan Community Scholars Program

Motawi Tileworks

MRun

Pall Biotech

PolyOne Corporation

Sustainable Living Experience

TBS Big Brothers and Big Sisters

UM Chi Epsilon

UM Circle K

UM Enviro 201 Class

UM Newnan Advising Center

UM Rotaract

UM Society of Wetland Scientists

Upcoming Conferences Sponsored by NAP:

The Science, Practice, and Art of Restoring Native Ecosystems Conference

January 17-18, 2020

This annual conference, at the Kellogg Conference Center at Michigan State University in East Lansing, covers a wide range of topics including environmental justice, watershed conservation, and much more! See www.stewardshipnetwork.org to register or for more information.

6th Annual Burning Issues Workshop

February 4-5, 2020

This annual workshop is designed to enable land managers, researchers, resource specialists, and fire practitioners an opportunity to hear and learn from different areas of expertise in a format designed to identify gaps in knowledge and communication, and work toward solutions. To register or for details go to www.firecouncil.org/events.

Staff Updates

Farewell...

Rebecca Snider, NAP Communications

Rebecca Snider, NAP Communications

I want to thank everyone for 2 memorable years at NAP. It's been a lot of fun working both in the office and out in the nature areas. I've learned so much about native plants and I plan to put this knowledge to use in my own garden. I'm returning to life as a full-time mom for now, but I'll be back as a volunteer. I'll see you in the parks!

NAP 2019 by the Numbers

- NAP staff and volunteers performed prescribed burns on 113 acres of land across 16 parks

- 1,926 volunteers have contributed over 10,254 hours

- 34 Breeding Bird Survey volunteers contributed 410 hours of effort and observed 190 species

- 40 Photo Monitoring volunteers contributed 191 hours of effort and submitted 555 photos from 20 different parks

- 10 Butterfly Survey volunteers contributed 73 hours of effort and observed 39 species at 7 parks

- 29 Frog and Toad Survey volunteers contributed 210 hours of effort and observed 8 different species at 40 sites

- 27 Salamander Survey volunteers contributed 215 hours of effort and observed 5 different species at 9 parks

- 15 Turtle Stewards contributed 143 hours of effort and observed 5 different species all along the Huron River