Protecting and restoring Ann Arbor's natural areas and fostering an environmental ethich among its citizens.

Volume 24, Number 3

Autumn 2019

Park Focus: A New Nature Area!

Krissy Elkins, Outreach Assistant

The creek flowing through the buttonbush woods, muddy during the rainy spring.

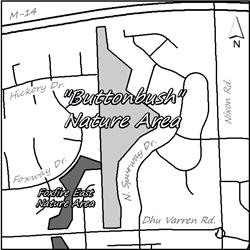

Pulling up to the shaded parcel of land at the end of Hickory Point Drive, I was happily greeted with enormous oak trees, shimmering maple leaves, and an abundance of excitement to explore this recent addition to our parks system. This new nature area is a piece of land edged near the corner of Nixon Road and Dhu Varren Road, tucked between a condominium development to the east, M-14 to the north and Foxway Drive to the west.

This nature area officially became a park in March of this year, but it is not yet offically named. The proposed name is "Buttonbush" after the beautiful buttonbush swamp in the eastern portion of the park. Athought it is commonly referred to as a buttonbush swamp after the dominant plant, this wetland feature is technically known as an “inundated shrub swamp." Water depth can vary according to rainfall and season, and these areas typically have acidic, sandy soil. Buttonbush flowers are small white balls, typically two inches in diameter. The native shrub blooms in late July, attracting all kinds of bee pollinators such as sweat bees, digger bees, and bumble bee. Although the shrub can grow in dry soil, it prefers a higher degree of inundation, meaning moist and mucky soils. Reaching as high as 15 feet tall, these thickets of shrubs can be tough to maneuver through, but they are a sight to see in late July!

A mature oak-hickory forest spreads across the north-western border of the park, sliced in half by a slow-moving creek. The watercourse, weak north of the buttonbush swamp, becomes wider and more turbid as it flows south through the park. Veering through Foxfire East and Foxfire South Nature Areas, the stream connects to Traver Creek, eventually emptying into the Huron River. Vernal pools dot this stream, some of which are home to amphibians, who will eventually make their journey into the upland forest. Undisturbed since at least the 1940's, the mature forest houses robust oak trees and towering shagbark hickories with a clear understory. Young, thin maple saplings can be spotted around every corner, with patches of sedges, May-apples, and false Solomon's seals sprinkled throughout the relatively flat ground.

As the creek twists and bends, contours in the land become more present. The heavier flow of the water cuts deeper into the earth, creating relatively steep hills alongside the creek banks. Moving south towards Dhu Varren Road, the landscape shifts from a wetland to a forest, struggling to keep out shrubby invaders like buckthorn and honeysuckle.

Despite the buzz of traffic from M-14 and the surrounding roads, hiking through this park feels like a nature sanctuary. Spider webs are carefully woven amongst the branches; sunlight streams through the overstory; Jack-in-the-pulpit springs from the earth; salamanders can be found under logs; it feels like a world away from the city. With easy access off Hickory Point Drive, this park and all of the native flora and fauna found within it is a must-see.

Join us for a workday at this new nature area on October 19. See the

calendar for more details.

A towering oak tree in this new nature area

Coordinator's Corner

Ann's Arbor- Part 2

Dave Borneman, Natural Area Preservation Manager

In the last issue, I described the native landscape that greeted City founders back in the early 1800s and led to them to choose the name “Ann's Arbor." It was a beautiful park-like setting with lots of grasses and wildflowers, where huge, wide-spreading oak trees grew 30-40 feet apart, and passage between them was “obstructed neither by bushes nor by fallen trees." A lovely setting, and very different than what now exists in most of our natural areas.

So, how do we get closer to restoring that native ecosystem that existed here only 200 years ago? How do we restore and maintain those open oak woodlands that gave Ann Arbor its name? In many parks, we still have big oak trees, so that's a start. What we lack are young oak trees. It's a matter of sunlight. Acorns need two things to germinate: contact with mineral soil, and sunlight. Acorns that fall on dense leaf litter in shady forests just won't grow. And if acorns don't germinate and grow into seedlings and then saplings, we won't have any big oak trees tomorrow.

If you're familiar with NAP, you won't be surprised to hear that returning fire to these landscapes is one of the most effective tools for getting acorns to germinate. Controlled burns remove leaf litter so acorns can get down to the mineral soil; and they let in more sunlight to the forest floor by setting back young shrubs, especially non-native ones. But fire alone will likely not be enough to maintain our oak woodlands long-term. NAP's controlled burns set back the shrubs and young trees, but they do nothing to reduce shade from bigger trees. In other words, fire alone is effective in keeping trees from becoming too dense in a woodland, but it is not effective in opening up those areas once they have become too dense with trees.

Study after study suggests that a more effective way to let in adequate amounts of sunlight is to combine controlled fire with the mechanical removal. That doesn't mean logging in parks. But it may mean exploring other ways to turn some of today's shade-producing trees into tomorrow's dead snags. Maybe we more aggressively go after other non-native trees in our natural areas, like sweet cherry or black locust. Or maybe we girdle some of the shade-loving maples that are encroaching into our oak woodlands (a process known across the Midwest as “maple invasion"). The resulting dead trees could remain (away from trails) for cavity-nesting birds and mammals.

Killing trees is controversial. Ann Arbor is a “City of Trees." We love our forests and do all we can to save big trees, including re-routing roads to avoid them or paying a lot of money to move individual trees that can't be avoided. So NAP is approaching this topic cautiously, thoughtfully, and slowly.

Ann Arborites today enjoy the large oak trees and the oak woodlands created by our ancestors and the Native Americans before them. What kind of landscape will we leave for our grandchildren? And how will we go about creating that for them? We'd love to hear your thoughts on these questions.

How Are Deer Affecting Our Wooded Natural Areas?

Dr. Jacqueline Courteau

Healthy urban woodlands provide many services to our city: they reduce soil erosion; offer a noise buffer along busy roads; and allow for cooler conditions. They offer places of natural beauty where we can connect with nature. And they are host to hundreds of species of wildflowers, trees, and shrubs. These plants provide food and habitat for diverse wildlife, including butterflies, birds, and small mammals, as well as deer.

Deer populations can increase in parks where they have no predators and hunting is restricted. Many park systems have found that deer are harming plants and species that depend on those plants. Deer can eat and trample plants, compact the soil, and disperse seeds of invasive species, such as the Japanese stiltgrass, recently discovered in Michigan for the first time. Deer are called browsers because they eat twigs as well as leaves. Heavy browsing reduces tree regeneration as well as wildflower diversity and flowering.

We have conducted several studies in Ann Arbor since 2015 to see how deer affect plants and the food webs that rely on them (including butterflies and bees). Key findings are highlighted here.

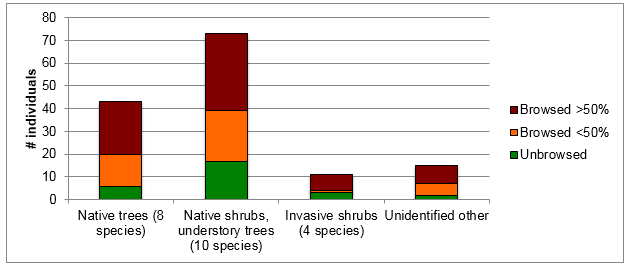

Bird Hills Nature Area, 2015:

We looked for deer browse damaged on tree saplings and shrubs of all species up to 6 feet tall – the deer browse zone. This survey of 142 individual plants found that 80% have been browsed by deer, and 51% have half or more branches browsed.

Most individual tree saplings and shrubs were browsed by deer. Browsing on more than 15% of tree seedlings per year may inhibit tree regeneration in forests, while damage on 50% or more of twigs or buds increases the risk of mortality and reduces flowering and fruiting of shrubs that supply nectar and food to native pollinators (bees and butterflies), birds, and small mammals.

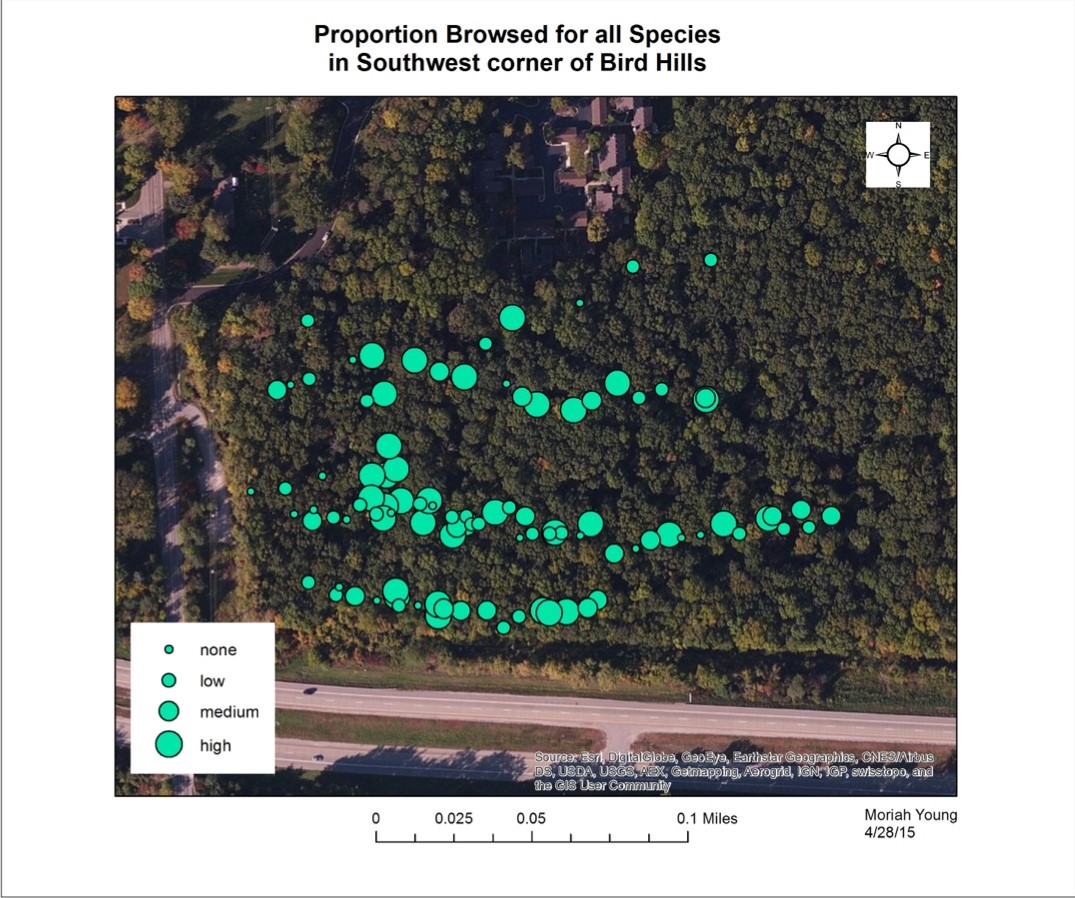

GIS map of browse intensity (% branches browsed) on trees and shrubs in Bird Hills, 2015).

Red oak experimental (“sentinel") seedlings, 14 natural areas, 2016–2018:

Red oaks are dominant forest species in southeast Michigan, offering food and habitat for many insects, birds, and wildlife. Deer damage on red oak seedlings can reduce or slow forest regeneration, and can also indicate the likelihood of deer browse on other plants. Red oaks are considered intermediate among deer preferences—browsed occasionally, but not strongly preferred. Therefore, we used experimental red oak seedlings as a standardized gauge of potential deer impacts across parks.

We grew and transplanted local-genotype red oak seedlings—456 of them in 2018—into wooded sites and monitored them 5-6 times over a full year to assess survival, condition, and signs of herbivory. We can distinguish deer browse from herbivory by rabbits, woodchucks, and voles—other critters that may chew woody plants—because deer lack incisor teeth and leave a crimped and/or shredded edge on leaves and twigs, rather than an angled cut or toothy gnaw.

In the 10 sites that we monitored for 3 full years, deer browsed more than half the seedlings overall each year. Research shows that oak forest regeneration is likely to fail if more than 15% of seedlings are browsed. Levels have declined in several sites over that time. White Oak and Huron Hills Golf Course Nature Areas continue to have the highest levels of deer browse, while Lakewood Nature Area has among the lowest levels. Deer browsing declined from 2017 to 2018 in Bird Hills, Black Pond Woods, Huron Parkway, and Furstenberg Nature Areas. Reduced deer browsing may be linked to deer management activities, and may also be affected by other activities (such as invasive shrub removal or changes in park use) that affect when, where, and how often deer browse. Annual variations in weather and rodent populations may also play a role. Experimental seedling data suggests that deer impacts may be declining in several parks, but levels are still high enough to affect tree regeneration and to indicate impacts to wildflower species.

Trillium study, 5 natural areas, 2016-2018:

Whereas red oaks are of intermediate deer preference, tender herbaceous wildflowers such as trillium, lilies, and orchids may be highly preferred. And while many plants can survive moderate deer browsing, it can still reduce their flowering and fruiting. Studies suggest that browse levels of more than 5-15% on trillium populations can lead to population declines or local disappearance.

To check how deer are affecting spring wildflowers in Ann Arbor parks, we located existing populations of trillium and set up pairs of unfenced and fenced plots with similar initial numbers in 4 City natural areas plus Nickels Arboretum. We revisited plots several times a year to count the number of plants (over 2,100 altogether), how many are flowering and fruiting, and how many are browsed by deer. Deer-browsed stems can be difficult to spot, but if you arrive on the site soon after the leaves are nipped off and get down on your hands and knees and look carefully, you’ll see them!

Browsed trilium stems. Left: Trillium in unfenced plot. Right shows the same plot, with each browse stem circled. The plot contains 12 unbrowsed trillium stems with 3 leaves, along with 27 deer-browsed stems. Chipmunks and rabbits may also eat trillium but damage marks can generally be distinguished. [Nichols Arboretum, May 2017]

At most sites, trillium abundance and flowering increased more in fenced plots protected from deer than in unfenced plots from 2016 to 2018. For example, at Bird Hills, where deer browse levels on unfenced plants were high (17%, 34%, and 22% for 2016, 2017, and 2018), total flowering levels in unfenced plots increased somewhat despite the browse (from 1 to 4) but jumped from 0 to 17 in plots protected from deer. (Numbers for 2019 have been recorded but are not yet included in these tallies.) At Black Pond Woods and Lakewood, trillium flowering increased in fenced plots while it decreased in unfenced plots. And at Mary Beth Doyle, the number of trillium plants increased in fenced plots but decreased in unfenced plots, although flower numbers were about the same. This study suggests that deer browsing is associated with declining trillium numbers and/or flowering in most sites, despite reduced levels of browsing on oak seedlings.

Fenced plot in foreground compared to surrounding area and unfenced plot in background. Plots had similar number of flowers at the start of 2016. Nichols Arboretum, May 2019.

Fenced plot in foreground compared to surrounding area and unfenced plot in background. Plots had similar number of flowers at the start of 2016. Nichols Arboretum, May 2019.

Wildflower experimental plantings, 5 natural areas, 2017-18:

While trilliums offer important resources to pollinators in the spring, summer wildflowers are also needed by a range of butterflies, native bees, and honeybees. We conducted a study to test how deer are affecting wildflowers and thus, potentially, the food webs that rely on their nectar and seeds. We set up five pairs of fenced and unfenced plots per site and transplanted into them 10 different species of local-genotype wildflowers of medium to high pollinator value and a range of reported deer preferences—a total of nearly 2,000 plants by 2018. We observed these plants 4-6 times during the growing season to record survival, number of flowers and fruits, and signs of deer browse.

While some species grew slowly or died back in the summer heat, heart-leaved aster, bluestem goldenrod, and zigzag goldenrod all grew enough to flower—and to be noticed by deer—so we analyzed these. In general, high levels of deer browsing (over 80% of unfenced plants across sites) did not outright kill the plants, but it did reduce the number and proportion of plants that flowered (compared to fenced plants). For example, at Furstenberg, deer browsed 95% of unfenced plants, so only ¼ as many bloomed as in the fenced plots protected from deer. And unfenced deer-accessible plots yielded just 12% of total flowers produced by experimental plants there.

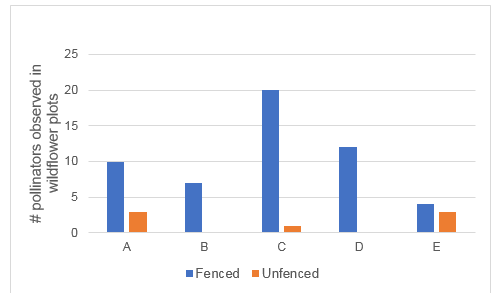

Lower flower numbers can reduce pollinator activity. A preliminary count of pollinator visits to flowers (observed in 15-minute intervals in Furstenberg) found significantly fewer key pollinators in unfenced plots, where there were fewer flowers —a total of 7 visitors—compared to 53 visitors to flowers in fenced plots.

Additional sampling is needed, but this pilot study suggests that deer can affect species beyond the plants they browse—a “trophic cascade." This is why many ecologists have referred to deer as a “keystone herbivore," a native but opportunistic species that can reshape the ecological communities where they live—including Ann Arbor's natural areas.

Pollinator visits recorded in 15-minute intervals at plots in Fursenberg, 10/3/2018. Pollinators observed included honeybees, bumblebees, halictid bees, syrphid flies, and a moth.

For more details, please see Dr. Courteau's complete report to the city.

Power to the Pollinators!

Becky Gajewski, Stewardship Specialist

We've all heard the recent news that populations of monarch butterflies and other pollinator species are declining worldwide. These reports are troubling to be sure – pollinators are necessary for supporting 75% of all flowering plant species, including most of our major food crops. But what can be done to help?

At NAP, we are supporting pollinator populations by working to restore and enhance pollinator habitat throughout our parks. Last fall, NAP was awarded a grant from the National Wildlife Federation to purchase native seed that would increase the amount and diversity of plants on which monarchs and other pollinators depend in our prairie, wetland, and savanna habitats. Over the winter and spring, the NAP crew spread seeds over 25 acres in five parks, so that the new plants, such as asters, goldenrods, coneflowers, and milkweeds will add additional support for pollinator species and help to grow their populations. We will continue to manage these habitats for invasive species and other threats, in order to give our pollinators and their plant hosts the best chance for survival.

And that's not all! The supervisory staff at both Huron Hills and Leslie Park Golf Courses are also conscious of the threats pollinators are facing. They have partnered with Audubon International to be a part of their Monarchs in the Rough program. Through this initiative, golf courses “donate" an acre of land in out-of-play areas to create habitat for monarchs and other pollinators. In return, they receive milkweed and wildflower seeds to plant in their donated acre. Milkweed has already been spotted growing in these enhanced areas, and the first sightings of butterflies happened in early June.

The situation is not hopeless for pollinators, but we must all work together to reverse the declining trends. So consider planting some native plants in your yard or garden! See this MSU brochure for some suggestions. Every bit of effort helps, no matter how small.

A monarch caterpillar on milkweed at the golf course

NAPpenings

Welcome, newPark Steward!

Eric Russell

Wurster Park

Thank You!

Many thanks to the gropus who volutneered with NAP recently. We could not make such a difference without you!

Ann Arbor Academy

Ann Arbor Open

Ann Arbor YMC-YVC

Community High School

DTE Energy General Operations

Duo Security

Eldor Auto

Fjallraven

Geocashing Community Service

MSCI

Plymouth YMCA

UM LSA Dean's Office

Unity in Learning Camps

Michigan Conservation Stewards Program

September 4- November 13, 2019

The Conservation Stewards Program is an eleven week course consisting of in-person classes, field days, and online coursework. This program will help you gain the skills to lead or contribute to land stewardship efforts in your area. For information visit the

program's webpage.

Staff Updates

Welcome...

.jpg?RenditionID=1) Josh Doyle, Crew Member

Josh Doyle, Crew Member

I have worked with GIVE365 for the last three years and I am thrilled to now be a part of the NAP team. The enthusiasm that Ann Arbor's citizens have for their parks is contagious. I am a future transfer student currently studying at Washtenaw Community College. My passion for improving and maintaining common spaces for us all to share has overflowed into my academic life. I am excited to continue to work with such passionate volunteers and staff to further better our parks system.

Matt Connors, Crew Member

Matt Connors, Crew Member

Growing up, I always enjoyed spending time in the forest or along the many lakes and streams of Michigan. After receiving my bachelors degree is environmental science ,I spent time with EarthCorps doing restoration work around the Puget Sound region and with the USGS collecting data on how sea level rise will affect wetlands along the Pacific Coast. Returning to Michigan has been a fulfilling way to reconnect with my roots. I look forward to working with NAP while exploring Ann Arbor's natural areas.

You're Invited...